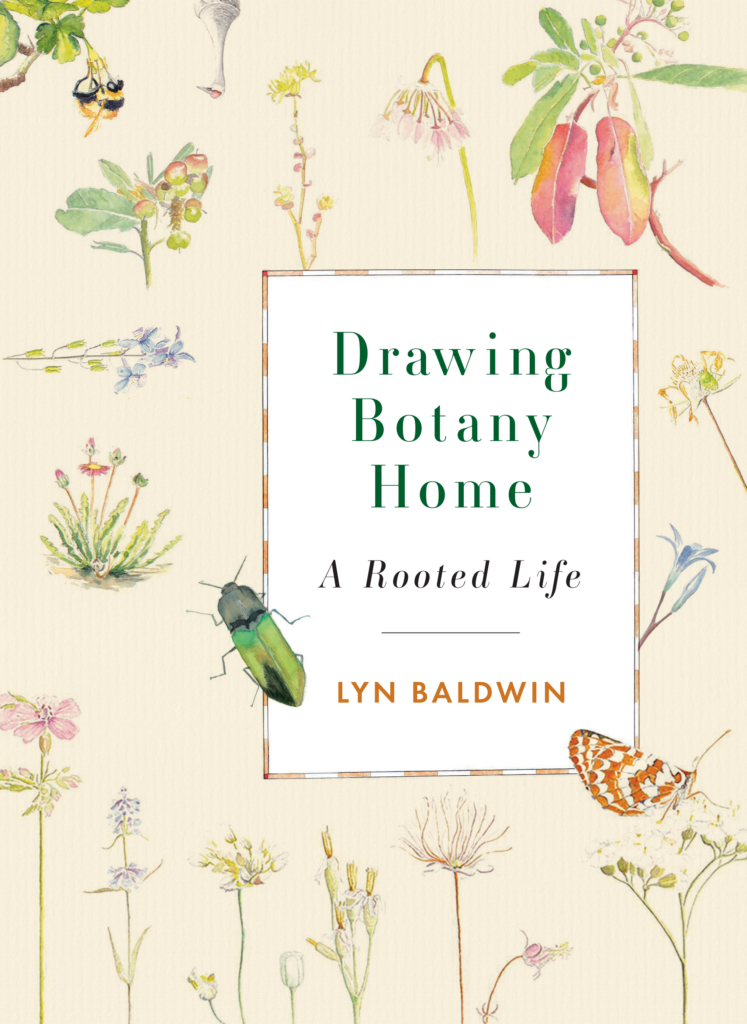

Coming April 25, 2023!

https://rmbooks.com/book/drawing-botany-home/

In celebration and anticipation, please enjoy this teaser from the book’s prologue.

(More to come each Teaser Tuesday)

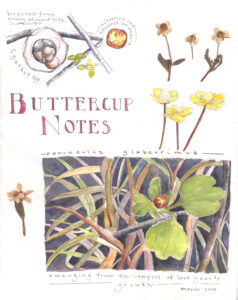

Prologue: The Comfort of Buttercups

(‘Reel’ available here https://www.instagram.com/p/Cm9nEYsN7X5/)

Ethnographers and geographers tell us that plants and place matter. Yet in a mobile world, both are easy to miss. In rural Montana, forty years ago, a Sunday afternoon erupts into conflict between my hippie mother and her American husband. When the argument turns ugly, I grab my younger brother’s hand flee out the back door finding comfort in the dependable appearance of spring-blooming buttercups.

Ethnographers and geographers tell us that plants and place matter. Yet in a mobile world, both are easy to miss. In rural Montana, forty years ago, a Sunday afternoon erupts into conflict between my hippie mother and her American husband. When the argument turns ugly, I grab my younger brother’s hand flee out the back door finding comfort in the dependable appearance of spring-blooming buttercups.

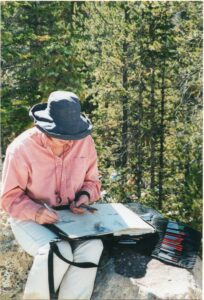

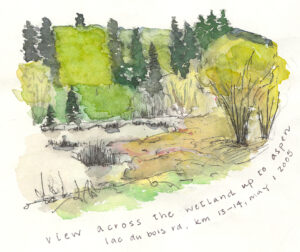

It’s the first time I remember running out the backdoor, but it won’t be the last. I will gain much from plants: comfort, academic credentials, even financial security. But for years, I will understand their botany as the scientific discipline I first learned far from home. Then, in 2004, when a new job gave me reason to return to southern BC, I thought I was returning home to teach botany and ecology. Little did I understand how close my homecoming would come to failing. Discouraged and homesick, I did what I’d always done as a hippie kid when things got hard: I ran outside. I never went far—rarely more than a day’s drive—but I went with my field journal.

It’s the first time I remember running out the backdoor, but it won’t be the last. I will gain much from plants: comfort, academic credentials, even financial security. But for years, I will understand their botany as the scientific discipline I first learned far from home. Then, in 2004, when a new job gave me reason to return to southern BC, I thought I was returning home to teach botany and ecology. Little did I understand how close my homecoming would come to failing. Discouraged and homesick, I did what I’d always done as a hippie kid when things got hard: I ran outside. I never went far—rarely more than a day’s drive—but I went with my field journal.  When my brother and I return to the most isolated of our childhood hippie houses in southern BC, recognition shudders through me. How many times, I wonder, did I flee family chaos for the tangled comfort of buttercups? How many of my family’s stories are woven with riparian willow and dogwood, shaded beneath a ponderosa pine, aching in the stubbled remains of a Douglas fir forest? Faced with plants infused with memory and meaning, I finally understood how drawing plants in place was more than mere comfort; it was a practice that could question my most deep-seated assumptions about home and family, discipline and practice, place and community. It also, I realized, allowed me to learn not just about, but from plants. As a botanist and artist in search of a rooted life, what lessons could matter more?

When my brother and I return to the most isolated of our childhood hippie houses in southern BC, recognition shudders through me. How many times, I wonder, did I flee family chaos for the tangled comfort of buttercups? How many of my family’s stories are woven with riparian willow and dogwood, shaded beneath a ponderosa pine, aching in the stubbled remains of a Douglas fir forest? Faced with plants infused with memory and meaning, I finally understood how drawing plants in place was more than mere comfort; it was a practice that could question my most deep-seated assumptions about home and family, discipline and practice, place and community. It also, I realized, allowed me to learn not just about, but from plants. As a botanist and artist in search of a rooted life, what lessons could matter more?

Come with me.