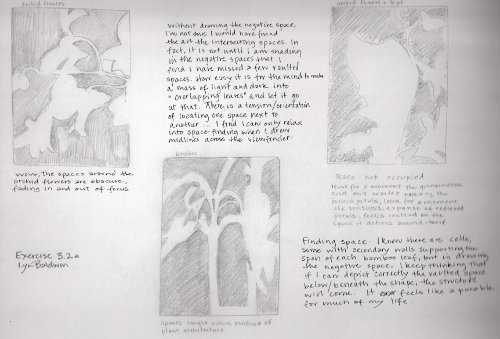

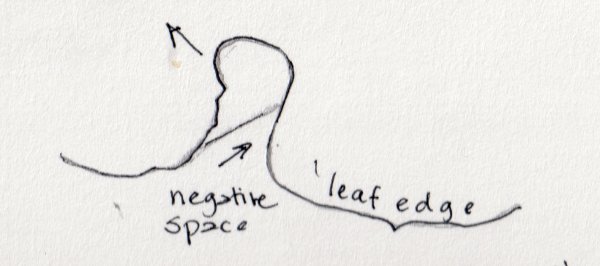

Is lived experience borne in the interior (the negative space) or in the exterior (the edges of form)?

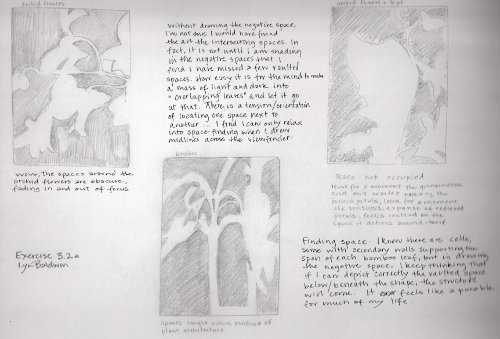

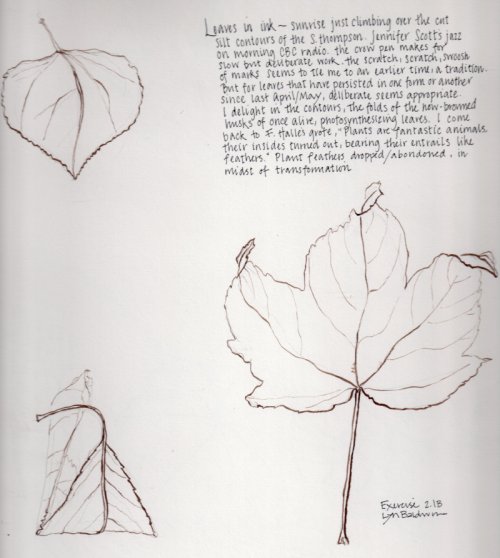

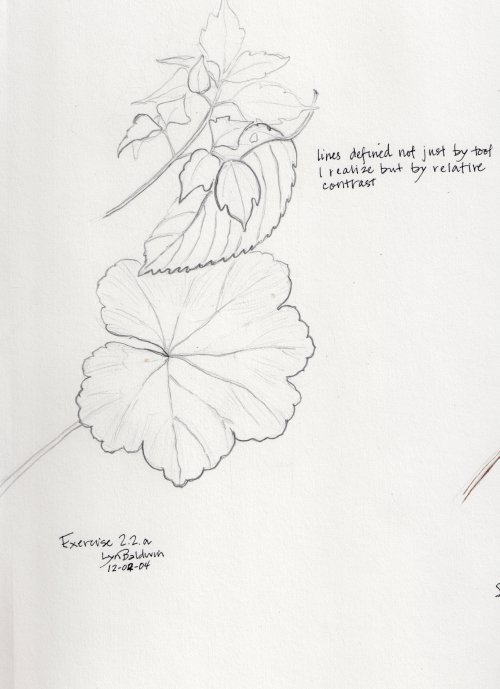

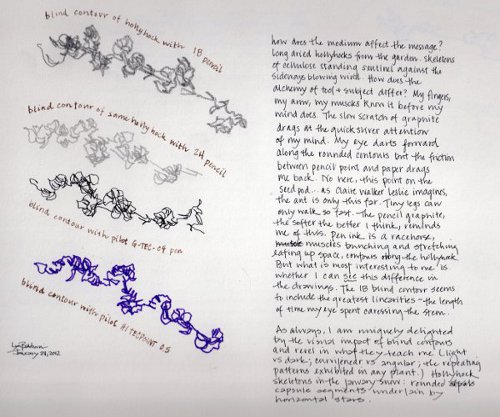

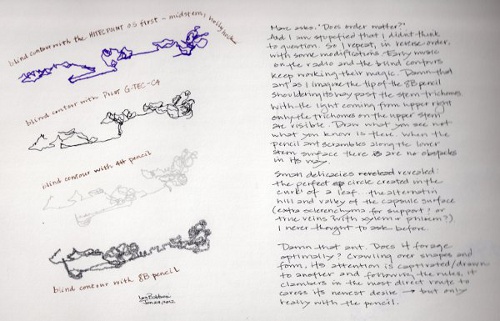

This week, mapping the negative space of orchid flowers, orchid flowers +leaf, bamboo, geranium, and asceplias, I found hidden forms/shapes caught within the confines of well-known plants. The bamboo shoot had vaulted spaces stacked atop one another. The inferior ovary of the orchid flowers became known to me through the space that its stair-stepped inferior ovary makes with the arching pedicel above. We are a story-telling species I tell my students, each time I know that I’m about to dive into arcane terminology. Know the terms so that you can hear the story. But how easy it is to gloss over the details. How easy it is for the mind to construct a mass of light and dark shapes into one—“overlapping leaves”—and skip merrily along. With each new negative space drawing, I found unrealized space.

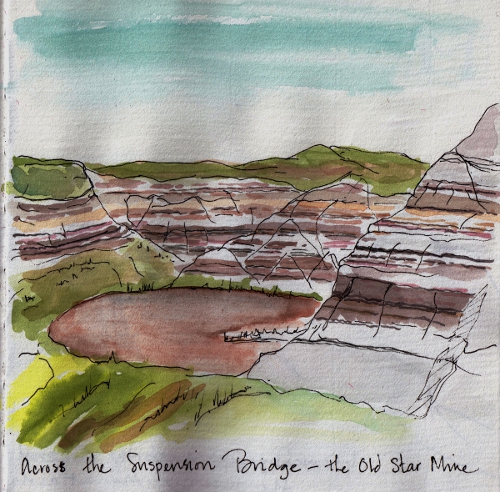

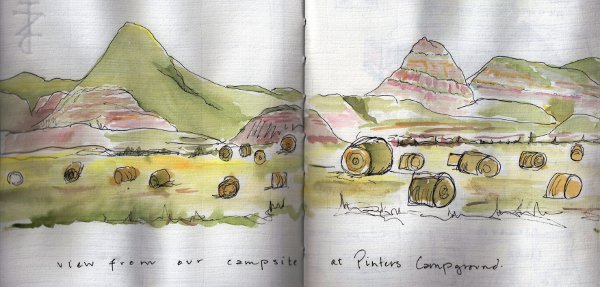

Space in relation to space. I was lost in negative space territory until I made midlines across the view finder and the space on the page. Then I feel myself settling into the known terrain of spatial orientation—this blob goes above that, that blob of space goes off in this direction relative to that. Finding space. I know there are structural ligaments—microscopic lines of cells with thickened walls and other cells ballooning with turgor pressure—that support the architectural expanse of each bamboo leaf, but drawing space somehow convinced me that it is the shape of negative space that supports the leaf. If I can trace the correct shape below, beside, above each leaf, the structure will come. It feels like a parable for my life.

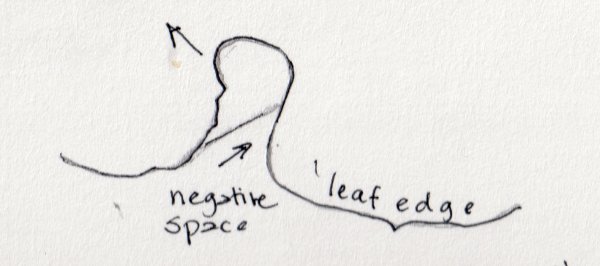

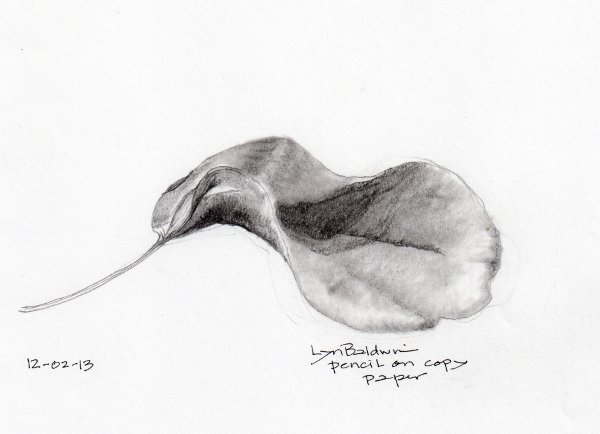

There is another story here. I think that negative space is to plant form as the process of art is to finished work. The fold in the geranium leaf is much easier to find when I focus on the space it encompasses than when my eye seeks the stability of the edge. In drawing the edge, I am seduced by the sharp contrast and gloss over the lighter leaf underside—the exposed belly. But when I squint my eyes to see the supporting shape, the fold of negative space is actually pointing in the opposite direction as the edge of the folded leaf. When I redraw that tiny piece in the sketchbook, the leaf fold becomes real.

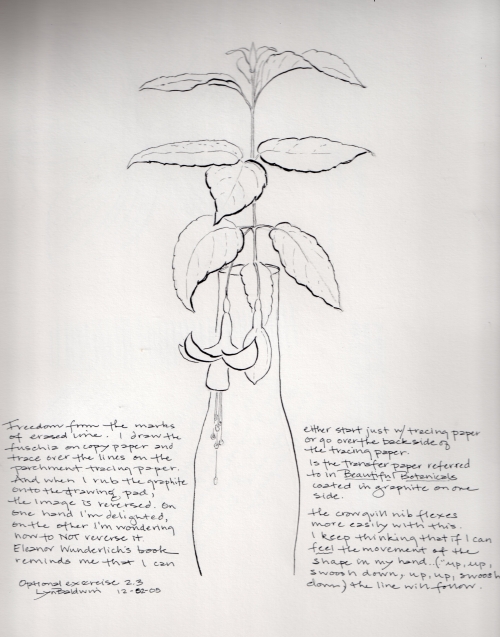

So much of what I respond to aesthetically envelopes authenticity. I’ve been casting about for a favorite piece of art and find I can name no finished piece. I don’t know that I have the language, visual or verbal, to elevate a particular work to favorite status (except of course any of Dale Livezey’s oil paintings of Montana and that’s because they so strongly evoke my childhood landscapes http://dalelivezey.com/recentwk.htm). Instead, what comes to mind, what I love to linger over are the sketches of any work in progress. Any of da Vinci’s sketches of course, but even in Picturing Plants, by Gill Saunders, the plate that stopped my breath was Jenny Braiser’s Cyclamen intaminatum page which includes both pencil diagrams, painted leaves and a complete colour chart for the cyclamen. It may well be that I am a slave of science—always pining for the elusive process that underlies the observed pattern—but I think it’s more.

The tracks of process—in a diagram or in the sketch that comes before a larger work—tell a tale about the lived experience. Art teaches me about the multiplicity about perception. My view of reality changes if I draw a geranium leaf from the front, from the side—and that’s with the same set of eyes. How does my student, my friend, a stranger see a geranium leaf? I know enough about plants to reject any Platonic ideal. There are lives captured in the gnawed edges of a leaf. What seduces me, what brings me to my knees, is the art that encapsulates the experience of both the painter and the painted. Art that can give me the little moments, the missed moments, is art I want to take home.

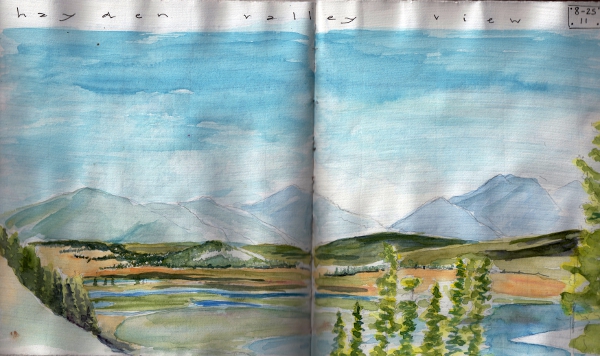

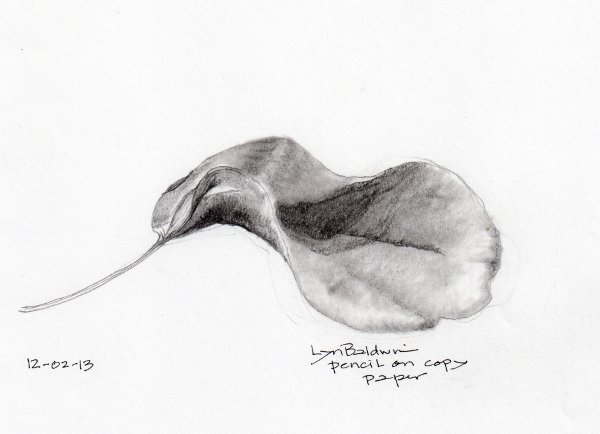

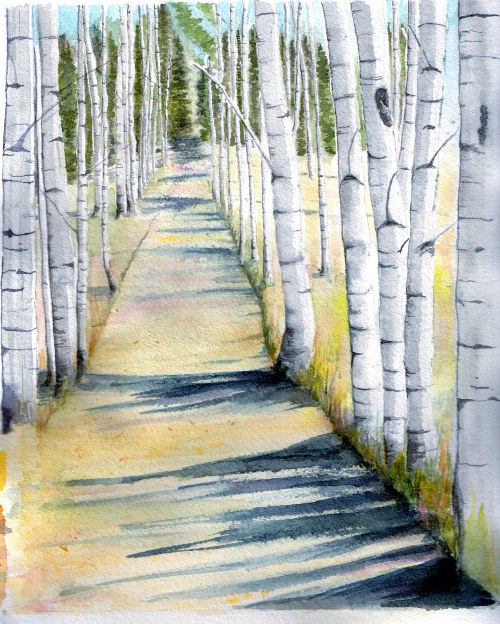

With the full fall of autumn turning into winter, work in my journal progresses with less completion. Instead trapped inside, I return to images collected from field days and work with them in larger format. For once, I can relish the relative sedentary of the cold season. Freed from the incessant need to see what is happening outside, I can play with colour and line, form and shadow. Aspen shadows results.

With the full fall of autumn turning into winter, work in my journal progresses with less completion. Instead trapped inside, I return to images collected from field days and work with them in larger format. For once, I can relish the relative sedentary of the cold season. Freed from the incessant need to see what is happening outside, I can play with colour and line, form and shadow. Aspen shadows results.