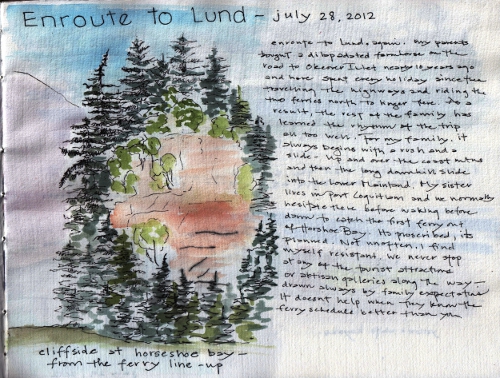

I can’t help it;in early March, the layered landscape of the Tranquille River burgeons with the beginning of spring, but oh so slowly. Out with Maggie and Marc and Shasta on the floodplain of the Tranquille River, the shape of the hills to the north are lyrical. Their colour, however, is of dust. This is a world in which green has been sapped by winter’s press. Home at my desk, playing with paint, I can’t help but push the colours further than reality. It is a exercise in wishful thinking, of dreaming in the spring.

The reality is one of layered debris. Nearly everywhere I look, I find the debris of the last fecund season.

Broken twigs of the last season litter the ground beneath the cottonwood trees; golden brown flower capsules curve on the ground.

This is a layered landscape, built of the shifting debris of the Tranquille River and the flooding Thompson River. Down on the delta, along the shores of Kamloops Lake, rocks pile in cobble bars and build terraces. Their forms are varied and I collect them, weighting my pockets with their history.

Each year, each beginning spring, I haunt this landscape. In the Thompson Valley, it is one of the first places to hear meadowlarks sing, to feel the sun ray’s build into warmth, to sense the building biology. We come out here often, but this is the first time, Marc and Maggie have come with me out to the toe of the Tranquille River. At 9:00 am, our walk is rich with biology: redpolls flocking, beavercut stumps, pileated woodpecker holes. There is the enormous eagle nest perched in a tall cottonwood and the hanging sock of an oriole nest.

Maggie finds an eagle feather in the debris; later I find another.

Two mature eagles and one juvenile soar and float overhead, intent on their own business.

In one week–from one Sunday to another, this delta, warmed by it’s south-facing aspect goes from slumbering to alert. I watch nearly an entire flock of blackbirds (mostly females with a few males–wing colours just coming on) raise up a ruckus in the cottonwood trees, juncos call, and the ducks gather in ever-increasing flocks on the small pond in the wildlife management area. Bighorn sheep cluster on the sleeps just above the CN tracks–remarkably nonplussed by the long train rumbling by.

It’s all a wash, a jumble of sediment and rock, a mix of decaying debris and returning life. I’m not the only one to spend spring days out here. By the time Maggie and Marc and I turn to walk back out to a car, the narrow parking lot along the road is filled. There is no denying that this land carries the trace of human activities, some recent, many more distant. Even so, there is such rich biology here, so much that it overwhelms, nearly exhausts a body trying to keep up. Layer me a land.

That day, there was little tree left. I could find pieces that I recognized—a terminal branch tip, scraps of bark still covered in tenacious lichens, and a few browned, but miraculously intact leaves from last year’s growing season. As startling as it was, this shattering was only the beginning of the cottonwood’s ruin. At the tail end of winter, the motor of decomposition idled slowly. But with the arrival of spring, as our oddly canted earth dipped its northern latitudes toward the sun, the chewers and the eaters and the decomposers rose up. Fungal hyphae spread. Bacteria proliferate, invertebrates tunnel. It might take several years, but the ruin of last winter will fuel other growth, other lives, until all evidence is erased.

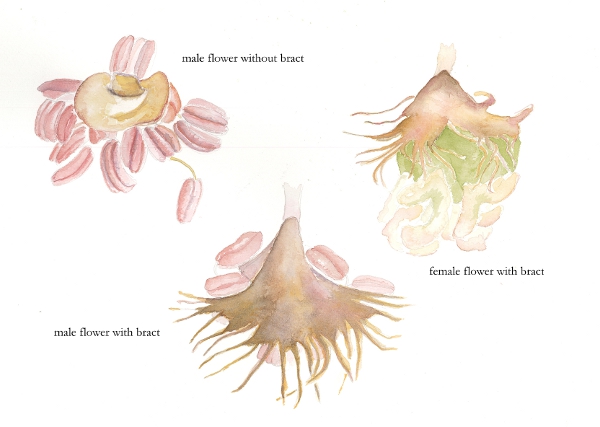

That day, there was little tree left. I could find pieces that I recognized—a terminal branch tip, scraps of bark still covered in tenacious lichens, and a few browned, but miraculously intact leaves from last year’s growing season. As startling as it was, this shattering was only the beginning of the cottonwood’s ruin. At the tail end of winter, the motor of decomposition idled slowly. But with the arrival of spring, as our oddly canted earth dipped its northern latitudes toward the sun, the chewers and the eaters and the decomposers rose up. Fungal hyphae spread. Bacteria proliferate, invertebrates tunnel. It might take several years, but the ruin of last winter will fuel other growth, other lives, until all evidence is erased. Male cottonwood twig with flowers

Male cottonwood twig with flowers