Sometimes the best gifts come as requests. In June 2016, I was asked to give a keynote field journal workshop for a group of tourism educators gathering to think broadly about care–care for their students, for themselves and the land that we walk, whether as residents or tourists.

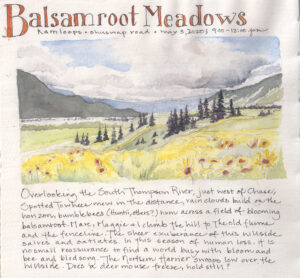

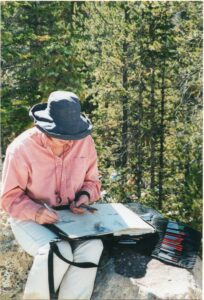

Photo credit: Jessica Silva

Being asked to give this keynote gave me permission to explore the history of field journals for what is known about the links between creative practices such as field journaling and care. The paper that I wrote describing these links (as well as the directions for a page spread in five exercises) recently came out and the publisher has provided a link for 50 free downloads. You can find the article here: http://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/TXih7dc9eU2xpEUf6asF/full

And the unpublished version (with colour images) can be found here (scroll down to where it says PDF)

http://tru.arcabc.ca/islandora/object/tru%253A1644

I’ve always valued my field journal as a tool for paying attention, but writing this paper help me understand why field journals can be so much more. Tourism educators (and others) talk about worldmaking or the processes by which what we do in the world shapes how we see the world. Goodman (1978) originally defined worldmaking as arising from the internal referencing inherent in any human activity whether it be science, art or craft. Much of it is unconscious, but every once in a while, something jars us out of the normal flow of our lives into “noticing.” Such interpretive encounters, suggests Kellee Caton (2013, p. 345, quoting Schwandt 2000) “always risk our previous ways of seeing the world.” Many have argued that what most needs jolting is our perception of the boundary between nature/culture as this artificial boundary (unsupported by empirical evidence) limits our ability to to connect to and care for the natural world.

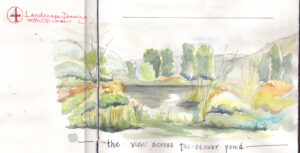

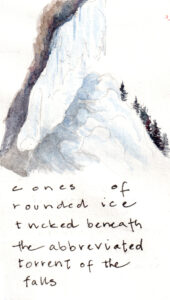

Here’s where I get excited. By mixing science and art, drawing and text, outward and inward attention, I think illustrated field journals invite the interpretive encounters that can help challenge this nature/culture dualism. As a practice, illustrated journaling is not just embodied, skilled, and creative (all attributes that have been linked with care), it’s also inherently place-based. Thus, my thesis is that illustrated journaling predisposes our worldmaking so as to recognize existing connections between people and place. In doing so, illustrated journaling facilitates the deep attending to the world that I believe is an important, and necessary, first step toward care.

Finally, speaking of not just care, but gratitude too. This paper is dedicated to my “litter-mates”—the extraordinary group of field journalers who gather each summer to carry this tradition forward. I am grateful to journal within your midst and I have learned from you all.

References cited:

Caton, K. (2013). The risky business of understanding: philosophical hermeneutics and the knowing subject in worldmaking. Tourism Analysis, 18, 341–351.

Goodman, N. (1978). Ways of worldmaking. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

For nearly four long years,

For nearly four long years,