Leaves of the pitcher plant, Saracennia spp.

My time in the Nova Scotia coastal barrens has me thinking about home and floras, known and not. In the barrens, with my hands and knees wet from the soggy ground below, the sensuous curves of the charteuse, red-veined, vase-like leaves of the pitcher plant were a miracle of attraction. When we found the sturdy flower stalks perched well above the leaves, a gleeful joy bubbled within. This I saw, amidst the larger tapestry of this exposed, soggy landscape not far from Peggy’s Cove, this I saw.

In this eastern maritime landscape, some of the flora I knew. The pitcher plants and huckleberries I had learned in similar wetlands in Vermont. Others I had forgotten or never knew. What was startling to me, amidst the tour of botanists, exclamations bouncing off the stunted vegetation, was how content I was to remain a visitor.

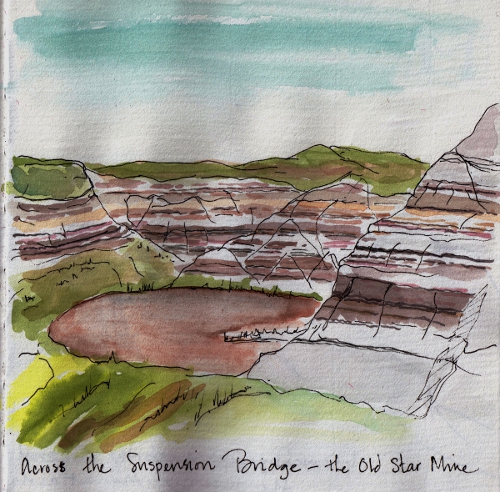

View across the barrens

In this place, spruce and Sphagnum, Drosera and huckleberry, Gaylussacia and Myrica, belong not to me, nor I to them. At home, in the dry grasslands and forests of interior British Columbia, the flora is both a comfort and a responsibility. The rhythm of a known botany is a constant companion. When I find a plant new to me, the excitement of the find also carries with it the burden of sorting through the taxonomic keys to find its name.

But in the barrens, not knowing all the names gave me permission to play. Pen scribbling in my field journal, I could relish the miniscule flowers of the sundew (who knew they were bright yellow!), the clustering of the spruce in islands of refuge, the delicate contours of the grass pink.

In the barrens, as a botanical tourist, my task was simpler. I was, as Linnaeus once described botanists, “much given to exclamations of wonder,” reveling in the subdued shapes and forms of flora I didn’t have to know by name.